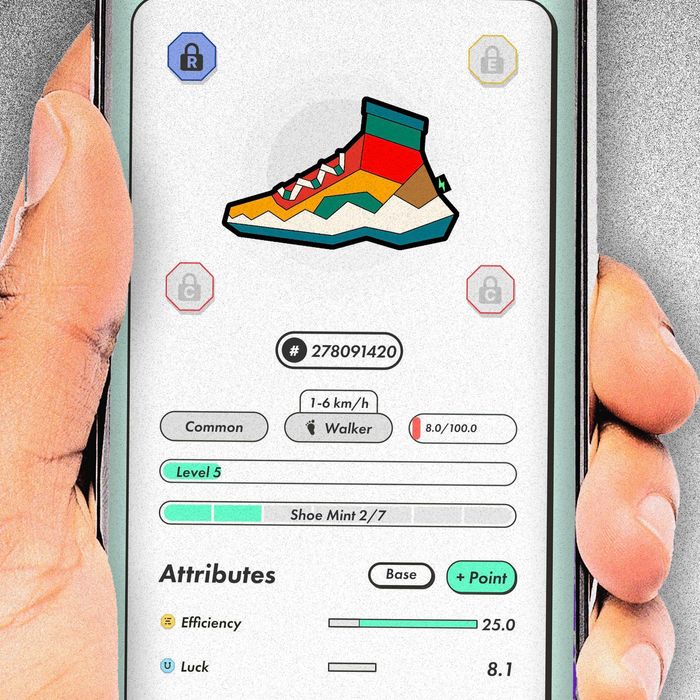

Author’s $ 200 NFT Sneakers.

Photo illustration: Intelligences; Photo: Kevin Dugan

Very few things have made people poorer faster this year than cryptocurrencies. What happened? It was the long boom from the pandemic in May 2020 to the peak of anything in November 2021, which was really a collective foam of many smaller bubbles. In retrospect, they blur a little, but each discreet mania had its own character, its own special way of earning and losing lots of money. It was the DeFi summer of 2020, when a vague finance-y group of companies seemed to make a few billionaires out of nothing more than moving around money. A year after that, it was the summer when NFTs were the thing and people convinced themselves that clumsy doodles and cartoons of monkeys had something to do with fine art. Along the way, it was the countless tokens that popped and fell in value – remember when Elon Musk ran the dogecoin on Saturday Night Live? One of the most spectacular outbursts was around “games to earn” crypto games, especially the not very fun ones. Axie Infinity, which centered around the breeding and breeding of NFT pets. They all tracked out of the petri dish known as web3, and they all saw the same end result: A few people got rich, but the chances are high that if you tried to ride the wave, you would be wiped out.

So when a new crypto trend called “move to earn” bubbled up this spring, there was all sorts of enthusiasm for it. (At that time, the crypto markets were down, but it was not yet clear to everyone that it was the early stages of a crash – that is, many people were still greedy.) It seemed that the trend was the first to drive the trend. be an app called Stepn, which paid you to go. As silly as it sounds, it was legitimate enthusiasm – some analysts said that, no, really, there was long-term value to it, and it was “helping people motivate themselves to exercise.” I did not exactly buy that there would be anything valuable with a blockchain-based system to pay people to go and run, but it had the support of the venture finance arm of Binance, the world’s largest crypto exchange, and Sequoia Capital, one of the largest and most respected VC companies on Sand Hill Road. Plus, when had a dubious core concept ever been a barrier to crypto success?

Because the move-to-earn bubble was just beginning to inflate at such an unfavorable time in major markets, this phenomenon never reached the insane heights of a Bored Ape NFT or a shiba inu coin, and probably never will. But it was a window into the state of the crypto industry at the end of its heyday. The appetite in the industry for the project existed despite the fact that there were no answers to any key questions: Why should a company in China care about how much I go? Why would they pay me for it? And why would anyone give them money for this whole project? The last crypto bubble has been driven by nothing but increasingly absurd promises to make easy money, a way to get around an economy that otherwise works you to the bone and makes everything unaffordable no matter what. Getting paid to go was too easy – and that was exactly what the appeal was.

I saw Stepn as my way of experiencing a part of the cryptocurrency world that most people do: without research, on blind impulses from someone looking for an easy way to make money. I read almost nothing about it online and instead chose to learn about it through what was available in the app under a page called “How to play?” It was not very complicated, but at least one of the catches was ready right away. Before you ever start making money, Stepn requires that you purchase a special NFT with a sneaker theme. (Recall, NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, are basically just unique digital assets associated with one of the various blockchain systems.) This NFT became your ticket to start earning Stepn’s cryptocurrency, which they call a green satoshi -token. There are a few different types of NFT sneakers you can buy, depending on how fast you think you are going to go. Hikers are for people who do not expect to walk faster than six kilometers per hour, which is about 3.7 miles per hour, a fairly normal walking speed. That’s the category I chose.

The sneaker NFTs have a kind of geodesic style and come with different “attributes”: efficiency, luck, comfort, resilience – all of which determine how much money you can make. The cheapest I could find on the market was around five solana – or a little more than $ 200 on the purchase. It was more than any actual sneaker I have ever paid for in my life. The most expensive were hundreds of thousands of dollars, but who knows if there were real prices. The process of doing even this little bit of currency exchange was demanding and difficult: I bought the solana through Coinbase, who informed me that it would take a week before my transaction was ready. After seven days, I bought a red, yellow and green high-top that had an efficiency rating of 25, which was the best I could find in that price range.

So on June 9th, a clear and humid day, I decided to walk from Park Slope over the Brooklyn Bridge to New York Magazine offices in Brookfield Place in downtown Manhattan, close to the World Trade Center.

Almost immediately, I noticed that the app’s tracker was off. Just about every time I checked the app, it clocked me to go faster than the 3.7 mph speed limit – although it was pretty clear to me that I was going slower than that. This is convenient for Stepn, since I would not make money going faster than that (there are other sneakers NFTs for these speeds I can buy).

When I got to the office, I ended the walking session and saw how much green satoshi token I had earned: zero. On the company’s Discord chat, I asked why that would have been the case, even after I bought the NFT for the sneaker, and a user mainly told me that I did not do my research. “Read the white paper. You need energy to earn. 1 shoe = 2 energy,” said the user, called PumpaSaurusRexx. White papers are a kind of user manual, but without any standardized language or format, so anyone who writes one can hide behind jargon as “1 shoe = 2 energy” without having to explain what it means in practice. (The rules I had read in the app did not mention energy or prescribed times or any rules around when you could start walking.) I told PumpaSaurusRexx that this was nonsense for me and the nerds shut in. Not only should I read the white paper, I should watch a long video of someone explaining all the rules. “The point is,” PumpaSaurusRexx told me, “you have started playing a game without understanding even the basics. “

How humiliating! It turns out that since I only bought one NFT sneaker, I only had the right to make money for ten minutes at a time, and I could only start doing it every six hours from 3 p.m. So not only do you have to pay hundreds of dollars just to start making money, you can only do so in short, specific windows. Suddenly the idea that I was making money on something I wanted to do disappeared. If Stepn told me when and how fast I should move, did it really make it to my boss?

Rude, I tried again. On June 13 – the day the crypto markets crashed – I walked around Brooklyn for well over ten minutes and earned a total of 8.05 green satoshi tokens – or, based on the market price then, around $ 4. If I had gone the same trip on May 24, when the tokens peaked at $ 29.10, I would have earned $ 234, or enough to justify the price of the NFT sneaker. When I tried to withdraw the money, the app informed me that I would not be able to transfer anything less than ten of the tokens, so I went again the next morning, and collected a much smaller catch of 1.9 tokens. Suddenly my NFT sneakers needed repair, and if I wanted to continue earning that much crypto, I would have to use more tokens for maintenance.

All the catches, the setbacks, the unfathomable jargon and the hidden fees – they reminded me of the worst in the financial industry, and corrupted people by tricking them. At the beginning of my business journalism career, I covered a niche type of bond called structured notes, which tended to be packed with derivatives that tracked the value of some stocks but were still sold to private investors. This was – and probably still is – a market with risky and complicated financial instruments. Part of my job was to read through prospectuses and find out how they worked: The typical bond would pay, for example, double the profit to Apple if the company’s shares rose past a certain point over a period of time. But they can also completely wipe out an investor if the value of the underlying company fell too much – a prospect that turned out to be quite real. It was common to see someone who was so insanely complicated that it was impossible for anyone other than a professional to understand them. Some included actual calculus equations as a way of describing how they worked. There were all kinds of triggers and catches, hidden fees and special ways to lose.

At one point, the Securities and Exchange Commission forced banks to simplify how they described these bonds and tell people that they were actually worth less than what they bought them for. Bond traders compared these notes to used cars or bottles of wine, things that lost money when you actually used them. It was not a serious comparison – the usefulness of an investment is, after all, in its ability to make money – but I guess it helped them justify tearing people off.

With Stepn, it was the same types of gimmicks – except that now they do everything without regulatory oversight and they call it a game. If you take a step back, there is a shocking amount of the crypto universe that seems aimed at real children – not just games, but the rappers and comedians who sell comics that cost as much as a mortgage. “If you get someone young enough, who was a young child in 2008 or who had never really invested in anything before, they may not know the difference between a responsible investment versus what we see in crypto,” Molly White, a software developer and Wikipedia- the editor who catalogs the absurdities of crypto countries on her page Web3 Is Going Just Great, told me. What’s amazing about all this is how randomly Stepn’s creators have acknowledged how similar the whole company is to a Ponzi scheme, even though of course they insist that they are different and completely ethical. (I sent an email to the company, as well as Sequoia and Binance VC, but got no response.)

Still, if you have the guts to read Stepn’s Discord channel, it really does look like something weird is going on. People are flooding the board with invitation codes – trying to bring in new users with more money – while complaining about how much the price of tokens has fallen and how little the NFTs are now worth. Others complain that they do everything right and still can not make money. “Most of the time I can not even earn. Gets very frustrating … idk man,” wrote one user.

I still have not paid out my 10.04 green satoshi tokens, now worth a little more than a dollar. And why should I? To give any VC at Sequoia the satisfaction of the transfer fee? I would probably just leave these tokens in my game wallet until they reach zero.