Tencent’s NFT platform halts primary services due to regulatory concerns

When China’s tech majors started selling non-fungible tokens, they said the products were not investment opportunities. This week, fans had to face a disappointing reality: the products aren’t really investment opportunities.

Chinese tech giant Tencent, the owner of WeChat, offered refunds to NFT owners on its Huanhe platform on Tuesday, nearly a month after it halted sales.

In a country that has banned all cryptocurrency trading since last year, perhaps that shouldn’t come as a surprise.

But buyers who were looking forward to profits from flipping digital art are disappointed.

When the shutdown was first rumored on July 21, NFT WeChat groups lit up with shocked messages. “None of us could believe what had happened,” Zhang Yeli, a 20-year-old university student who had spent 5,000 yuan ($740) on the platform, told Sixth Tone earlier this month. “Tencent can’t just shut down the platform like some small sketchy companies do. At the end of the day, it’s the biggest tech company in China.”

Huanhe’s digital collectibles were never marketed as investments, to comply with strict Chinese rules prohibiting speculation in digital assets, which include a ban on cryptocurrency. In fact, there was no way for Huanhe buyers to resell their purchases. Once the products are purchased, they are permanently linked to the buyer’s account. But that didn’t stop speculators from betting that the platform would one day allow resale.

It seems that Huanhe will continue to exist in some form without an NFT market. In a statement provided to Sixth Tone, Tencent said Huanhe is making “business adjustments” and that “according to internal sources, these adjustments do not involve a reduction in the number of employees.”

Some see the ongoing incident as an alarming signal to the entire industry. “It will restore interest in the sector as collectors see that even a Tencent-backed platform can close its core business suddenly,” said Xiao Gao, founder of Flame DAO and member of the Conflux Network. “The impact I think is still somewhat limited because the digital collectibles market in China is still quite small, not even comparable to the NFT markets abroad.”

Xiao is a crypto community organizer who has managed several high-profile NFT projects that connect digital assets to real-life physical activities.

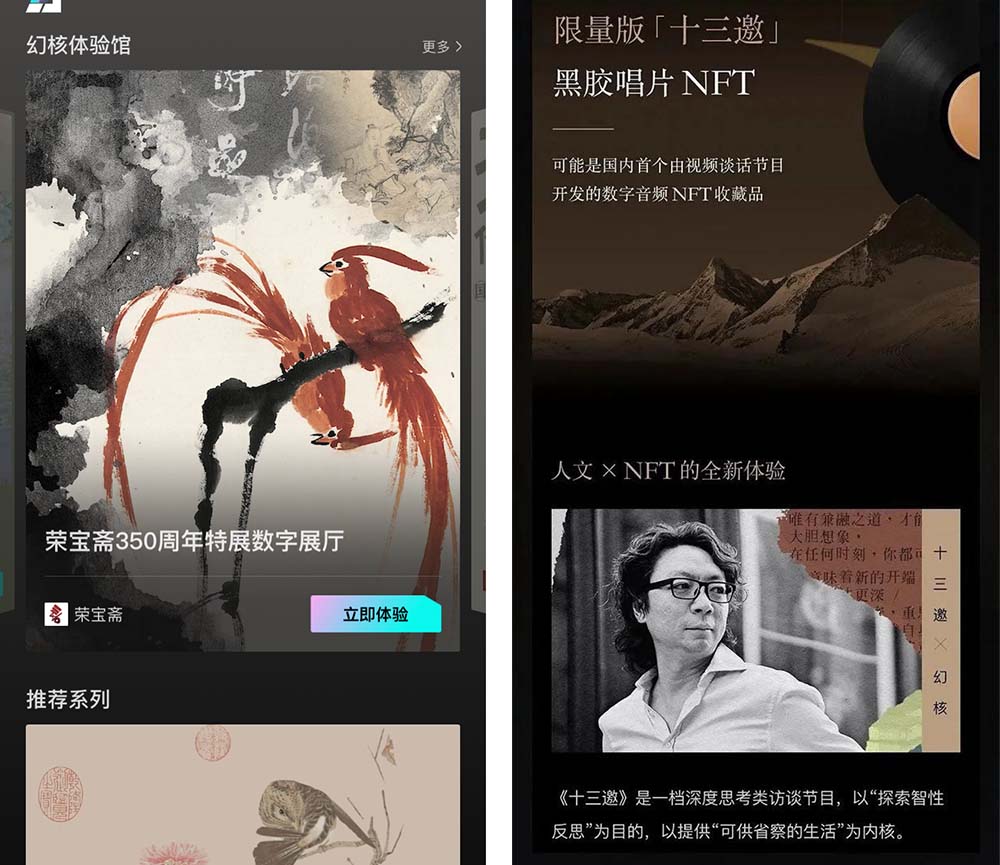

Left: A screenshot from Huanhe; right: A poster showing an NFT product sold on the platform.

Buy low, never sell

NFTs are a controversial spin-off from the world of cryptocurrency. Essentially, an NFT is a certificate of ownership, which identifies the holder as the owner of an associated thing, often a digital object that anyone can see.

For advocates, they are the future of art collecting, among other things. People have sold NFTs associated with artwork, trading card-like cartoons of monkeys (and lions, and cats, and so on), and even more intangible concepts like the destruction of a diamond. To skeptics, they are Beanie Babies with no practical uses, a sham of ownership that gives the owner no special rights.

Last year, enthusiasm for the new technology spurred prices for NFTs to record highs, allowing early buyers to profit. But most Chinese investors were left out, as local regulations prohibit trading in cryptocurrency, which is necessary to buy most NFTs, as well as “speculation” in digital assets.

Chinese buyers wanted in on NFTs, and a number of Chinese companies found a way: Tencent created a closed platform for “digital collectibles” — a term used in China to refer to NFTs — that could never be resold. Without the ability to flip the token to make money, there can hardly be speculation.

Most Chinese digital collectibles are built on permissioned blockchains, meaning users can only access the blockchain via permission granted by the network owners. According to Tencent’s terms and conditions, all collectibles on the platform are for “research, study, appreciation and personal collections only.” In addition to not supporting any kind of trading and asset exchange, the company reserves the right to suspend all or part of its services at any time without taking any responsibility for users’ losses.

Ant Group, the Alibaba-affiliated financial services company that owns Alipay, offered only marginally more permissive rules on its rival platform, Jingtan. Jingtan allows users who have had a collectible for at least 180 days to give it to another user, as long as the other user does not pay. Only after holding an asset for two years can the recipients transfer them again, and still only as a gift.

In April, Gen Z favorite video platform Bilibili announced plans to release 10,000 NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain – but only to foreign users.

Huanhe was an instant hit. The first sale, a 300-item collection based on the well-known talk show Shisan Yao last year, was so popular that the platform accidentally accepted more orders than it had in stock and had to compensate buyers.

Many buyers assumed it was only a matter of time before the platform would change its policies to allow reselling.

“When I bought collectibles at Huanhe, I aimed to keep them for at least ten years,” Zhang said. “If I put the money into another sketchy platform, they could have just taken my money and run away, but Tencent definitely didn’t want that because of the credibility. Believe it or not, the people who came to Huanhe were actually long-term value investors.” Zhang said the 5,000 yuan he spent on Huanhe was about 10% of the money he invested in NFTs.

In a release shared with Sixth Tone, Tencent reiterated that Huanhe had said it would never open up a secondary market for users to transfer digital collectibles, “nor support any illegal activity related to cryptocurrency.”

Ma Ximing, 26, an insurance agent who paid more than 10,000 yuan to buy a series of digital versions of Monet paintings in April, said he expected competition would eventually force Huanhe to allow resale.

“Huanhe had to catch up to attract traffic, I thought, by opening secondary markets,” Ma said on August 7. “After seeing collectibles on other platforms increase over tenfold in a matter of days, I thought it could happen on Huanhe one day as well. It’s all about timing and getting there early.”

There is no moon

It didn’t work out that way.

In May, Huanhe’s sales dried up, with unsold images crowding the digital shelves.

A major problem was competition from smaller platforms that encouraged reselling and speculation. From February to June this year, the number of such platforms increased fivefold to over 500.

Of course, they weren’t all up to par. Several collapsed or ran away with the customers’ money. “TT Digital Collectibles” disappeared in a single concise WeChat post that read: “Our boss has allocated a seed fund worth one million yuan to invest in the digital collectibles platform IBOX. Due to unstable market conditions, the investment is now worth only 100,000 yuan. Our platform is shutting down and the technology team has already been laid off.”

Scandals like these attracted the attention of regulators. In a joint statement, China’s banking, securities and internet finance associations pledged to curb “the financing of NFTs,” but did not directly address yuan-denominated digital collectibles.

With poor sales and looming legal problems, Tencent began pulling the plug in May. It ended several sales ahead of schedule, declaring the collections “sold out.” On July 21, Chinese media Jiemian reported that Tencent was in the process of shutting down Huanhe, citing internal sources familiar with the matter.

Some vented and cursed in the group chats for a few days after the news broke, Zhang said, but as time went on they began to accept reality. Tech outlet 36Kr reported that a collector offered to sell an account he had spent 150,000 yuan on for 100,000 yuan to someone willing to bet that services would resume and secondary markets would one day go live.

On Tuesday, Tencent confirmed that it will end the sale, and announced that users can apply for refunds for purchased collectibles. Android and iOS users can expect to receive refunds within seven and 20 days, respectively, the platform said.

At press time, all existing collections on the platform are marked as either “closed” or “sold out”. Tencent’s statement reads: “User ownership will not be affected by the business adjustment because all the metadata of digital collectibles are already recorded on the blockchain.”

The announcement also stated that Huanhe would destroy all the collectibles on its blockchain after users receive the refund. Soon after the news made headlines, Huanhe’s forum on Tieba, a Chinese Reddit-like platform, was instantly revitalized with a flood of comments from once-disappointed users who cheered the official announcement as “the end of the drama.”

Huanhe HODL

Some die-hards say they have no plans to return the NFTs – just in case the platform backs down and opens a secondary market one day. “I will keep all five of my collectibles, worth 460 yuan. The worst thing is that I want to lose them all. Let’s see,” wrote one Tieba user.

Zhang says he will try again. “Obviously, I am disappointed that Huanhe terminated his services,” he noted. “But Huanhe exiting digital collectibles does not indicate a failure for the entire industry. I am moving the payback to other promising platforms.”

However, Ma admitted that the announcement left him relieved. Unwilling to reveal the total amount he had spent on collectibles, Ma said he is disturbed by the fact that even giants like Tencent can be subject to unexpected turbulence due to political changes.

“The market in China is still a gray area, and politics is not on our side. Tencent could have just walked away without compensating us, and we couldn’t have done anything about it. …”

Zhang and Ma both said they felt a bit like they were in a cult, and they tried to keep the topic away from family and offline friends.

“I’m not even sure if I can make money from it. Why would I drag the people around me into this?” Zhang said. “To be honest, I don’t have any friends in real life to talk to about digital collectibles.”

Editor: David Cohen.

(Header image: VCG)