Singapore court says NFTs can be ‘property’

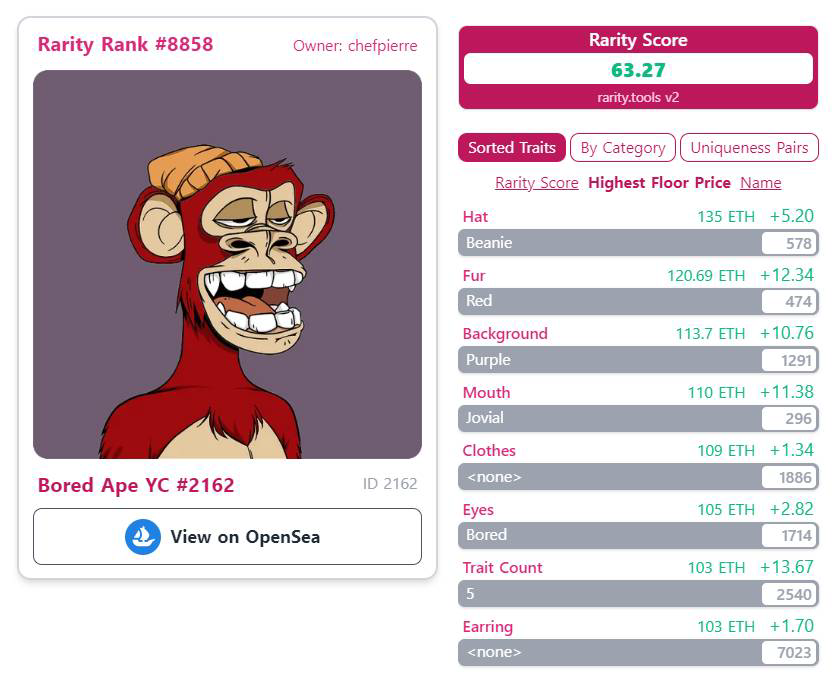

An interesting new decision by a court in Singapore sheds light on the nature of non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) and the applicability of existing laws to such relatively new technologies, with the High Court of the Republic of Singapore ultimately ruling that NFT – can be considered property and thus “be subject to a proprietary injunction”. The NFT in this case is Bored Ape #2162, which plaintiff Janesh Rajkumar claims was taken from his possession when he “foreclosed” on a loan – for which the NFT was used as collateral – that he received from the defendant, chefpierre.eth. Exclusively identified by its ENS domain, chefpierre then listed the NFT for sale on OpenSea, prompting Rajkumar to seek an injunction preventing him from “dealing with Bored Ape NFT in any manner” for the duration of the case.

In his decision on October 21, Judge Lee Seiu Kin sided with Rajkumar, ordering the defendants to refrain from selling the NFT, which has since been frozen from trading on NFT marketplace OpenSea. The court set the stage, stating that while “cars, books, wine and luxury watches … are a few examples of highly sought-after items for collectors, [f]or digital nomads, especially those steeped in the blockchain and cryptocurrency world, NFTs have emerged as a highly sought-after collectible.” Using an analogy, Judge Kin says that certain NFTs “are equivalent to a Rolex Daytona or an FP Journe for a watch enthusiast.”

To address some additional background, Judge Kin claims that in a previously decided case he addressed the issue of whether stolen crypto-assets, specifically Bitcoin and Ethereum currencies, can give rise to property rights and therefore be subject to a proprietary injunction. ” In that case, the court found that the plaintiff “was able to prove a serious arguable case that the stolen cryptocurrency assets were capable of giving rise to property rights that could be protected via a proprietary injunction.”

The matter at hand “repeal[s] similar problems,” according to Judge Kin, who is “not surprisingly given the rapid pace at which modern technology is developing, disputes arising out of the use and deployment of such new technologies will become more common.” Against this background, the judge maintains that ” the pressing concern that most lawyers will face” – in relation to NFTs and web3 more generally – is “whether the substance of the common law can be extended, in a principled way, to cover disputes involving these technologies.” (In light of the outcome of this round of the Bored Ape NFT case, as well as the stolen crypto case, both of which resulted in a finding of title to the digital assets and preliminary injunctions for the plaintiffs, it appears the answer is yes. )

In connection with its injunction decision, the court claims that the plaintiff had to show that he has “a serious arguable case that he had a property right” in Bored Ape NFT, which “naturally rests[s] provided that the Bored Ape NFT, or NFTs in general, are capable of giving rise to property rights.”

NFTs: information or property?

As for what NFTs actually consist of, the court asserts that “in most cases and certainly in this case, all an NFT contains is a link to the server there [an] actual the image can be found,” noting that “although dealing with an ‘on-chain’ NFT, it is essentially a string of code that includes the code for the image.”

With this in mind, Judge Kin says that “it can be argued that all that is acquired when one ‘buys’ an NFT is merely information.” If NFTs “are characterized as information, one can expect to find serious objections to giving it property status,” according to the judge. “But where cryptoassets (i.ecryptocurrencies, tokens and NFTs), it may not be entirely appropriate to characterize them as information.”

At this point and quoting the result of Ruscoe v Cryptopia Ltd.where the New Zealand High Court ruled that cryptocurrencies, like digital assets, are a form of property at common law, the judge gives his opinion, holding that “NFTs, when distilled to the base technology, are not just information, but rather data encoded in a specific way and securely stored in the blockchain ledger.” Here the court similarly points to Amir Soleymani v. Nifty Gateway LLC the case, as well as the note order from May 2022 i Hermès International and against Mason Rothschildin which Judge Jed Rakoff of the US District Court for the Southern District of New York denied Mason Rothschild’s motion to dismiss Hermès’ claims against him, holding that while there may be an “artistic aspect” to the images associated with the MetaBirkins NFTs, Hermès, nevertheless, pleaded sufficient cause for trademark infringement, dilution and cybersquatting.

Doubling down on his decision, the judge states that “to characterize NFTs as pure information would ignore the unique relationship between the encoded data and the blockchain system that enables the transfer of that encoded data from one user to another in a secure and verifiable fashion.” ” And although there may be grounds for treating information as property, such a provision “depends on the functions [the information] used for rather than on the simple fact that it is information.” In the context of NFTs, the information in question is “a string of computer code (in its essence, zeros and ones) that conveys no knowledge to those who have read it,” according to Judge Kin, but simply “gives instructions to the computer under a system where the ‘owner’ of the NFT has exclusive control over the transfer from the wallet to any other wallet.”

Against that background and in light of “increasing legal support for ‘distributing property concepts to protect digital assets,'” the court sided with Rajkumar and agreed to grant an injunction, shedding light on how NFTs are treated in the process in jurisdictions outside the United States

The case is Janesh s/o Rajkumar v. Person Unknown (“CHEFPIERRE”), 2022 SGHC 264.