How London lost its luster to fintechs

When Silicon Valley Bank UK imploded in early March, fintech start-ups were among those scrambling to get cash out of the troubled US lender that specialized in financing the technology sector.

“I spoke to the CEO of the fintech on Friday dinner – he assured me that everything was fine,” said one founder. A few hours later, his company only had three months’ wages available, with £2m locked up at SVB UK, the bank’s local subsidiary.

SVB UK’s £1 fire sale to HSBC stabilized the situation, securing deposits. But the relief has been marred by concerns that one of the few lenders willing to back innovative start-ups faces an uncertain future, subordinated to a giant in Britain’s banking sector.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak launched a review of UK fintech when he was chancellor, calling for a “digital big bang”. His chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, has since spoken of Britain’s “world-beating fintech sector” in a speech envisioning “the world’s next Silicon Valley”.

But fintech entrepreneurs say that, despite the right noises from the government, much more is needed to ensure the UK retains its pre-eminence in fintech, from unlocking extra funding to reforming listings.

“I think everyone is a bit tired,” said Christian Faes, chairman of mortgage lender LendInvest, which is set to list in London in July 2021. “There was no doubt that London was the center of fintech[ . . .]It has been declining for several years.”

SVB Great Britain

The fintech founders emphasized that the HSBC deal was far better than SVB UK going bust. But several raised concerns about how well the cultures of the two banks would integrate, given their different risk appetites and backgrounds.

“Many founders who said they were recently rejected by HSBC now have accounts with them through SVB UK,” said one investor. “Do they now have to look elsewhere, or is this something HSBC will be comfortable with?”

Philip Hammond, a former British chancellor and chairman of crypto firm Copper, also questioned whether HSBC could provide the kind of support needed for riskier early-stage companies.

“Companies are asking themselves whether, despite all the rhetoric, it will be possible for the rather peculiar culture [of SVB UK] to flourish inside a behemoth like HSBC,” he said.

HSBC said it intends to continue to run SVB UK as a standalone entity with no changes to its approach to customers and that the bank will continue to support businesses in the same way as before the acquisition.

“We have a long history of supporting innovative start-ups in the UK and around the world,” it continued, “and we have always had strong working relationships with venture capital and private equity firms.”

But the future of SVB UK’s clients is not fintech’s only gripe, with some founders drawing attention to uncertainties stemming from the UK’s departure from the EU.

“Tech skills are in short supply and in some ways that’s limiting growth potential, particularly for fintech in the UK,” said Mark Mullen, chief executive of digital bank Atom.

Government reforms

These challenges are unfolding at a time when growth stocks have taken a beating globally, as rising interest rates and soaring inflation have led investors to seek short-term profits over long-term growth.

Swedish fintech Klarna had its valuation reduced from USD 46 billion to less than USD 7 billion in its funding round last July. UK payments fintech Checkout.com, last publicly valued at $40 billion in January 2022, cut its internal valuation to $11 billion last December.

“Inflation may not directly affect a fintech company, but if they have to pay 50 percent more for energy and consumers want to save instead of spend [ . . . ] which is likely to filter into fintech activity, says Nalin Patel, an analyst at PitchBook.

Fintechs are also calling for more comprehensive reforms to support growth, such as pushing pension funds to invest part of their funds in UK companies, including fintechs.

“There is a genuine desire in government for the UK to be a global financial centre,” Mr Hammond said. “but there seems to be no will to understand what is necessary to achieve it.”

Charlie Mercer, head of economic policy at start-up lobby group Coadec, also warned that changes to the research and development tax credit announced by Hunt in the spring statement would prove a particular challenge for fintechs, which are unlikely to spend enough on R&D to qualify.

“Data from our survey of over 250 start-up entrepreneurs found an average cut of 30 to 40 per cent in funding received, with an average cut of £100,000,” he warned. “This time next year could be bleak for many firms.”

Entries

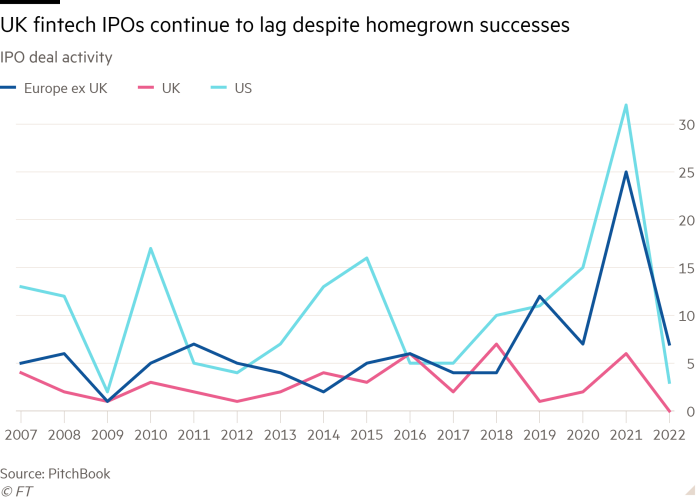

One of the most difficult areas of discussion has been around ensuring that fintechs choose London over other markets when going public; a debate that companies in other sectors also weigh in on.

“You’re just not going to get the same level of investor demand, liquidity and valuation in the UK,” said one fintech executive. British tech giant Arm chose New York over London, with strict rules said to have influenced the rejection of the British float.

Ron Kalifa, the former Worldpay CEO, led the fintech review commissioned by Sunak. Kalifa proposed changes such as allowing dual-class share structures to allow founders to maintain greater control over their companies after an IPO. The government and financial regulators have taken some steps to address some of the issues he raised.

For example, since December 2021, the Financial Conduct Authority has allowed premium-listed listed shares to have dual-class shares, although they are required to drop the structure after five years.

Another of Kalifa’s recommendations led to the launch of the Center for Finance, Innovation and Technology in February.

Despite these adjustments, Atom Bank’s Mullen said the problems ran deeper.

“The question is whether London is a hub for global businesses and businesses that want to be global,” he said. “I’m really not sure – the noise seems to drown out sensible debate.”