China activists use NFTs, decentralized technology to counter censorship

Chinese activists are using NFTs and decentralized technology to document and preserve details of protests over Beijing’s zero-Covid lockdown rules that erupted in several cities and universities over the past week and turned into criticism of the Communist Party’s rule and leader Xi Jinping.

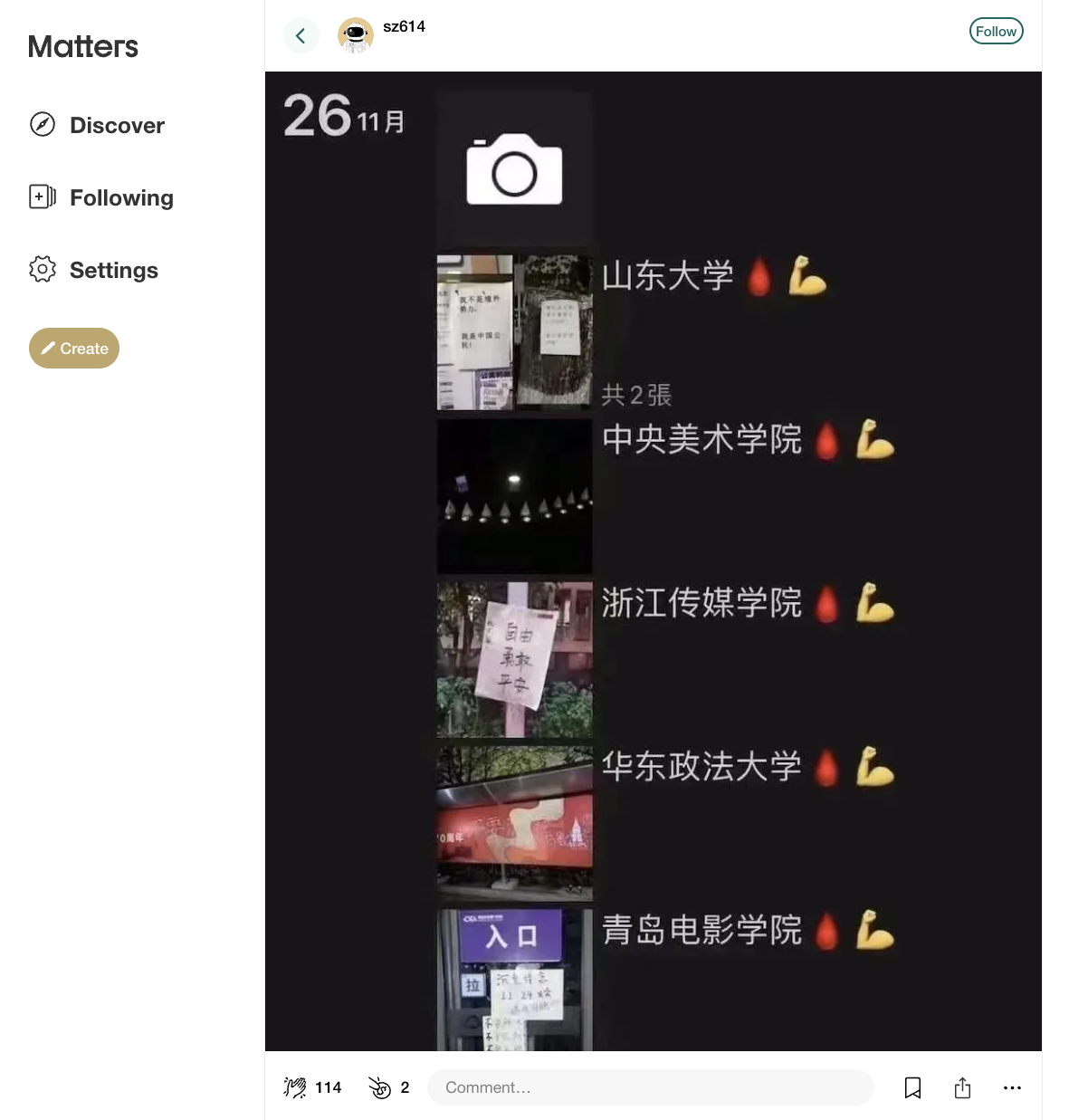

Protesters post articles and photos on Matters, a US-registered decentralized content-sharing platform built with the Interplanetary File System, or IPFS, which has been referred to as the Airbnb of cloud data storage.

“When you’re in a place where information is censored, you naturally want to archive and back up content,” said Annie Zhang, founder and CEO of Matters. Discard.

The rare public protests erupted after an apartment fire on November 24 in Urumqi, the capital of China’s Xinjiang region, killed as many as 10 people, prompting accusations that Covid-19 lockdowns had prevented people from escaping the building.

An article on Matters said: “Those who rose up were devastated, not just because ‘some citizens don’t have the ability to save themselves.’ They also became aware of a fact that they had ignored all along: when we repeatedly back down, sooner or later it would be your turn to fall off the cliff.”

NFT collections related to the protests are also available on OpenSea, the world’s largest NFT marketplace.

They include “Silent Speech” and “Blank Paper Movement”, both coined based on images related to the protests. Silent Speech is a collection of 137 NFTs, and Blank Paper Movement consists of 36 stylized images that drew inspiration from protesters holding up blank sheets of paper to symbolize the suppression of free speech.

Censorship antidote

Demonstrations initially focused on the nation’s zero-Covid policy, which could result in city-wide lockdowns and quarantines even if isolated cases are detected, but they soon escalated into direct criticism of the ruling Communist Party. Such actions in China can lead to arbitrary arrest and imprisonment.

Videos and images of the protests circulated on the Chinese internet, which is cordoned off by China’s government from the global web in what is known as the Great Firewall. The video and images were quickly removed by censors.

“Some posts related to protests were taken down within minutes of being published,” Zhang said.

Decentralized content platforms, such as Matters, can be used to counter censorship, given the immutability of decentralized technology and the fact that the content does not live on a single server, making it difficult to delete or modify.

As of Wednesday, dozens of articles about the protests have been posted and trending on Matters’ platform.

An article published on Sunday showed WeChat screenshots of a collection of footage of protests taken from the streets of dozens of universities across the country.

“Many people are writing about their lives or moving articles that were censored on WeChat to our platform,” Zhang said.

“Some people say that the least they can do now is to write and document, and that is also a process of self-empowerment,” Zhang said. “It seems to me that the meaning of documenting has evolved beyond simply leaving a record or an archive.”

Launched in 2018, Matters is no stranger to hosting such content and has become increasingly known as an outlet for getting around censorship, especially in China.

As early as 2019, users began posting about China’s MeToo movement and backing up important files on the platform. The platform also hosted posts related to protests in Hong Kong in 2019, followed by comments surrounding the 2020 coronavirus outbreak in the Chinese city of Wuhan.

In April, Matters users also published content related to the censored “Voice of April” video, which composed audio conversations and complaints from Shanghai residents as they faced weeks of Covid lockdown.

While the “right to be forgotten” remains a burning issue for users in certain regions, Zhang said in an April interview with Discard that “the right to ‘be remembered’ is a more pressing and urgent matter.”