Blockchain and new trends in money

Last week we concluded Part 1 with the observation that perhaps the most disruptive aspect of digital transformation is its implications for the concept of money. With an expanding platform, Bitcoins, Ethereum and Ripple threaten to challenge fiat money, that which is issued by the various countries’ central banks.

Do these digital assets have what it takes to be accorded the same trust as fiat money to fully serve society?

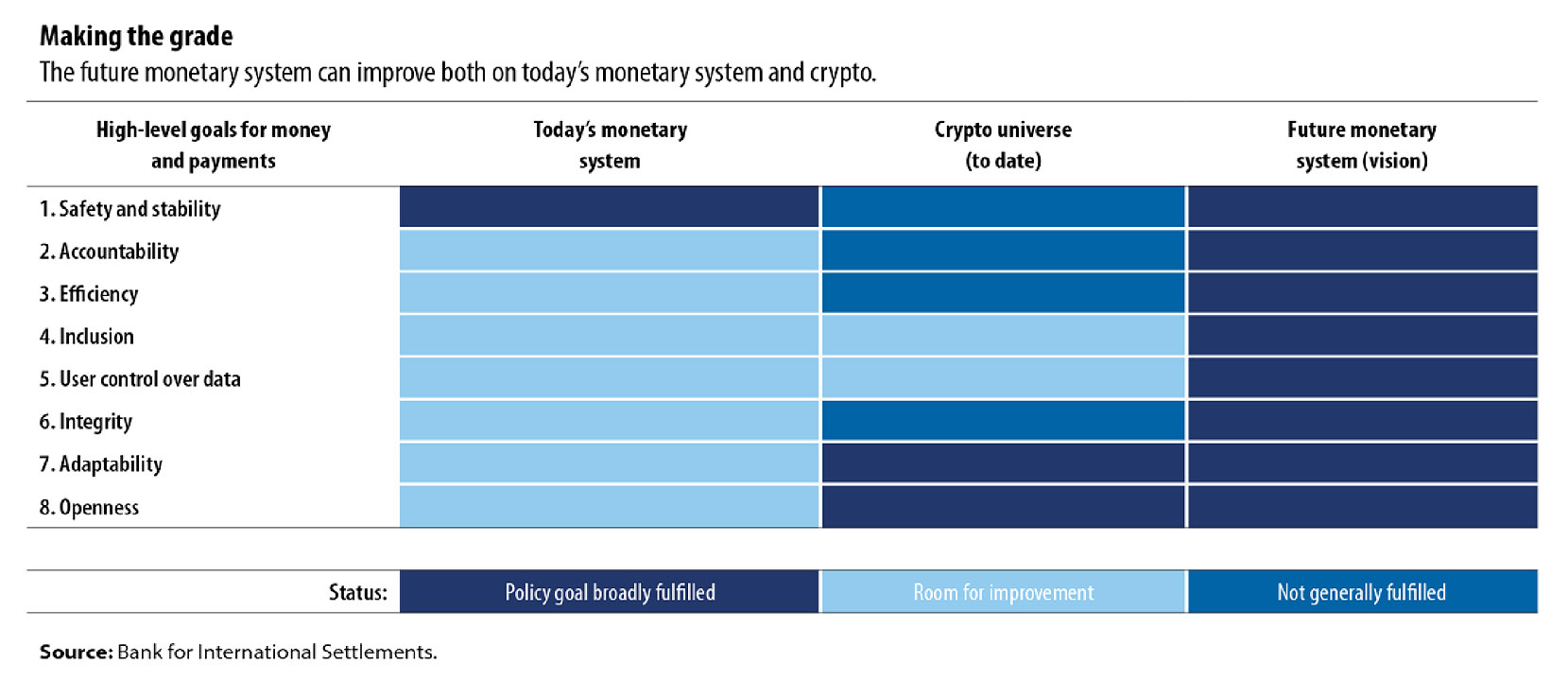

The literature is unanimous in saying that security and stability are important features of a money claimant, whether public or private, which should be accountable to the public. As Agustin Carstens, Jon Frost and Hyun Song Shin of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) argued in the IMFs Finance and development September 2022, a money pretender must also be efficient and inclusive with participants in control of their data. Fraud and abuse are delimited. To be global, it must support cross-border transactions.

Carstens, Frost and Hyun were quite categorical that “today’s monetary system is generally safe and stable, but there is room for improvement in many areas”.

To transition from what we have today to a future monetary system with stronger accountability, efficiency, inclusion, user control over data, integrity, adaptability and transparency, the so-called crypto universe can be exploited for its adaptability and transparency for cross-border transactions. .

As for the rest of the functionality, the crypto universe is claimed to be structurally flawed. The BIS argued that, firstly, it has no nominal appeal as it uses cryptocurrencies and the so-called stablecoins which in turn piggyback on a sovereign currency such as the US dollar, or an exchange-traded commodity such as precious metals. And here’s the rub from the BIS: cryptocurrencies are not currencies while stablecoins are not stable. The BIS cited the reported implosion of TerraUSD last May as markets continue to question the support of the largest stablecoin, Tether.

In short, “stablecoins seek to ‘borrow’ credibility from real money issued by central banks.” The BIS was fully justified in saying that if central bank money didn’t exist, someone would have to invent it to make the crypto universe somewhat viable.

Second, the cryptosystem motivates fragmentation. The BIS rightly pointed out that money is indeed a matter of social convention, that its widespread use further propagates itself as a store of value and a medium of exchange, that this popular acceptance depends on the fact that its stability, security and finality of settlement are all guaranteed by a reliable institution such as the central bank.

In the absence of such a central entity, and crypto’s decentralized nature given its reliance on anonymous transactors to confirm completion upon payment of fees and charges, congestion is inevitable. The incentives need to be scaled up significantly, although this may effectively prevent wider use. With higher costs, nothing prevents the transactors from switching to other blockchains, resulting in fragmentation.

Therein lies crypto’s shortcoming. Its stability and effectiveness may be subject to question and doubt. Unregulated, the crypto universe is run by participants with no established accountability to the public. And in light of reported incidents of fraud, theft and various scams in recent years, we share the BIS’ concern for market integrity.

For this reason, the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s (MAS) Ravi Menon, in the same IMF publication, called for caution against any delay in meeting the challenges of crypto-innovations. “Central banks and regulators cannot afford to wait for clarity on how crypto-related innovations will shape the future of money and finance.” They are sweeping the economic landscape with great speed.

MAS recognizes the great potential of digital assets to enable more efficient payment transactions. MAS said that in the areas of cross-border trade and settlement, trade finance and capital market activities, the use of blockchains could reduce settlement time from a few days to less than 10 minutes and cut costs from 6% to less than 1% of the transfer value. Within trade finance, the processing time for letters of credit has been shortened from five to 10 days to less than 24 hours. In the case of capital market transactions, clearing and settlement of securities transactions has been reduced from two days to less than 30 minutes. In other business areas, digital transformations in Singapore have allowed automatic execution of, for example, coupon payments, when pre-set conditions are met.

However, like BIS, MAS argued that privately issued cryptocurrencies fail as money – or as a medium of exchange, store of value or as a unit of account. They are no more than tokens of blockchain projects, but because “they are actively traded and heavily speculated on, with prices divorced from any underlying economic value on the blockchain,” they could not pretend to be either tokenized currency or investment property. For MAS, stablecoins have better potential provided they are appropriately regulated and supported by good reserves to which they are linked. But such a link could also pose a risk to stablecoins. When liquidity problems strike, stablecoins may have to be sold at a loss.

Which brings us to Cornell University’s Eswar Prasad who pointed out in the same IMF publication that a payments infrastructure run entirely by the private sector can be efficient and cheap, like cryptos and stablecoins, but “some parts of it could freeze up in case. of loss of confidence in a period of financial turmoil.”

This means that if digital currencies were to dominate the payment and settlement landscape, and stability and trust become an issue, it is possible for a modern economy to literally freeze. Prasad pointed out that if only to prevent this impasse, central banks should consider issuing digital forms of central bank money for retail payments, or central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). Should private money fail, central bank currency may well offer a public payment alternative. It can also help promote financial inclusion and increase the efficiency and stability of the payment system. CBDCs can prevent illegal activities such as drug deals, money laundering and terrorist financing. More and more financial activities can be flushed out of the gray market and moved into the formal economy.

CBDCs also have their weaknesses. If the banking public decides to patronize CBDCs instead of keeping their money in regular bank accounts, the commercial banking system would be starved of their main source of loanable funds. Central banks may end up allocating credit and in the process discourage digital innovation. In addition, CBDCs can lead to a loss of privacy. Currency-issuing central banks will always want to ensure that their digital currency is only used overboard.

Most importantly, central banks should be able to design correct monetary policy as lending platforms continue to go digital, reducing the role of commercial banks in financial intermediation. More research is needed to determine how monetary policy transmission will evolve and affect even the nature of money without affecting its ability to promote price stability and sustainable economic growth.

Prasad’s closing point is sobering: “Financial innovations will generate new and as yet unknown risks, especially if market participants and regulators place undue faith in technology.” A decentralized and fragmented payment system works well in good times when market confidence is not so much of an issue. In bad times, confidence can drop, especially when digital currencies are not backed by reserve funds.

As the BIS emphasized, central banks remain indispensable in leveraging both digital transformation and their role as monetary authority to foster such a core of confidence in the market. Markets are confident that central banks will generally do their job as issuers of sovereign currency, providers of the ultimate payment infrastructure, and regulators and supervisors of financial services and their instruments.

The Philippines’ Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas may not yet find the need to issue CBDCs given the generally well-functioning payment systems and adherence to the broad principles of financial inclusion. What may be more urgent is to start building a technological infrastructure that will enable the issuance of retail CBDC should it be necessary, especially when conditions warrant it.

It is not long-term for the digital asset ecosystem to develop as a fixture in the Philippine financial system, even alongside the regular banking intermediation system. But sensible preliminary work in developing frameworks that seek to balance the risks and opportunities offered by digital transformation is the only path to a brave new digital world.* n

* For example, MAS has launched an initiative, Project Guardian, to assess possible digital asset applications in wholesale finance markets. DBS Bank, JP Morgan and Marketnode are leading this project, which involves creating a liquidity pool of tokenized bonds and deposits locked in a series of so-called smart contracts. This is aimed at achieving seamless secured borrowing and lending of these tokenized bonds through smart contracts.

Diwa C. Guinigundo is former Deputy Governor of the Monetary and Economic Sector, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). He served BSP for 41 years. In 2001-2003 he was Alternate Managing Director at the International Monetary Fund in Washington, DC. He is the senior pastor of Fullness of Christ International Ministries in Mandaluyong.