Black NFT artists think they are this generation’s hip hop

Ethat same year, people from all over the world make a pilgrimage to a green Harlem brownstone on E. 126th Street in hopes of conjuring up history. It was there in 1958 that 57 jazz icons, from Thelonious Monk to Dizzy Gillespie, gathered to take a now iconic photo for Esquire Magazine. Forty years later, hip-hop royalty including Rakim, Grandmaster Flash and A Tribe Called Quest hit the same steps for XXL Magazine, asserting themselves as generational inheritors of black artistic excellence.

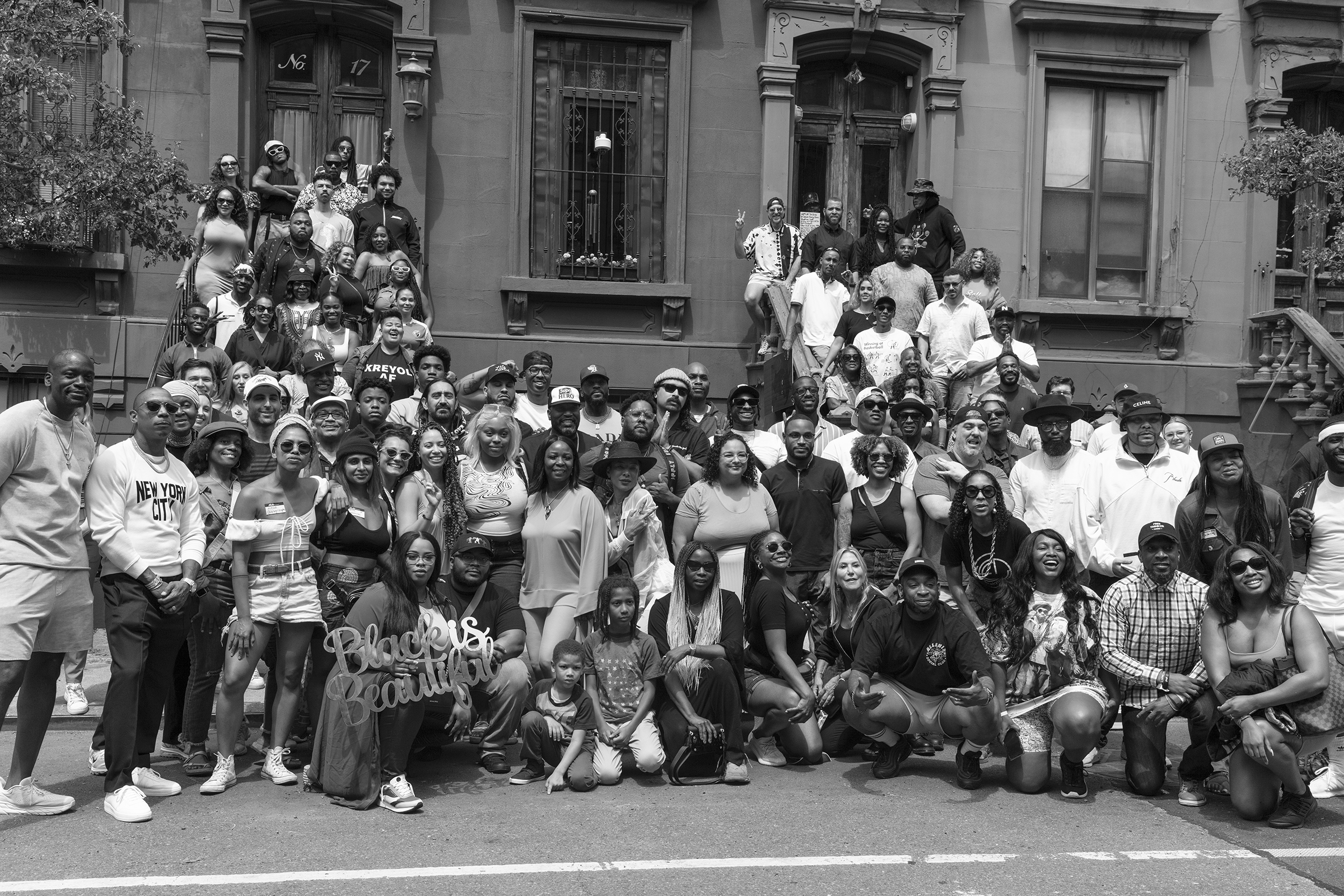

In June, a new group took to the stairs hoping to tap into the same legacy: Black NFT artists. Such a declaration might give some skeptics pause. Crypto has been one of the top cultural lightning rods of the year, as the crypto market has fallen aggressively, hacks and thefts have increased, and pyramid schemes have fallen on themselves.

Black NFT artists gather at 17 E. 126th St in Harlem for a photo shoot led by Brandon Ruffin. Iconic portraits of jazz and hip-hop musicians were taken from the same pole in 1958 and 1998.

Gioncarlo Valentine for TIME

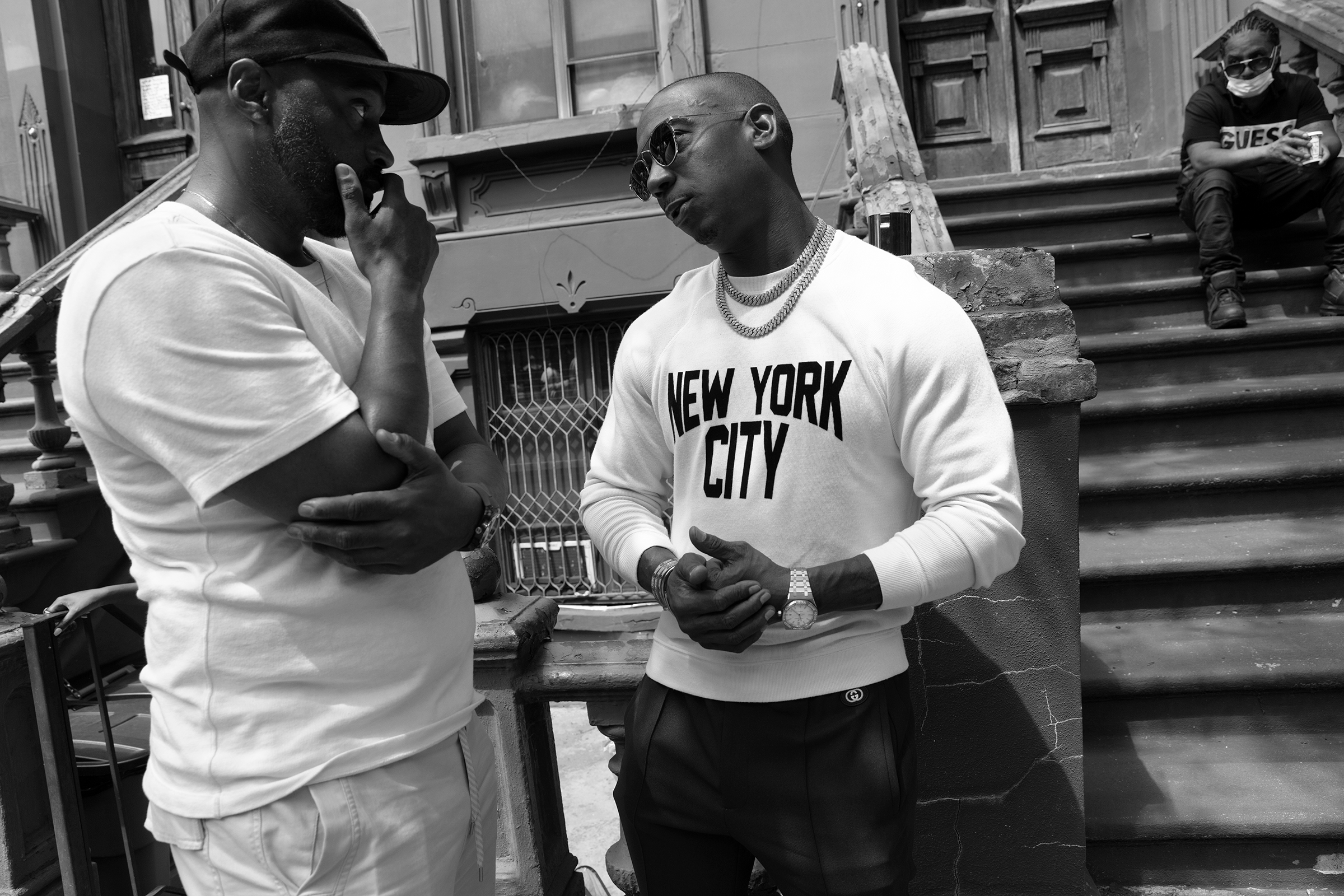

But these artists and crypto-builders are certain there’s an unequivocal thruline between jazz, hip-hop and the so-called Web 3. They say crypto could hold the key to a brighter, more resilient future for black artistry, and are adamant about continuing to bring their peers on board, bear market and naysayers be damned. “It’s the same: It started from nothing,” says rapper Fat Joe, standing solemnly under the brownstone steps just as he had for the hip-hop shoot 26 years earlier. Referring to NFTs, he said: “It’s actually the only place where you can find a level playing field. It’s time to bring awareness and let everyone know that there are opportunities for everyone.”

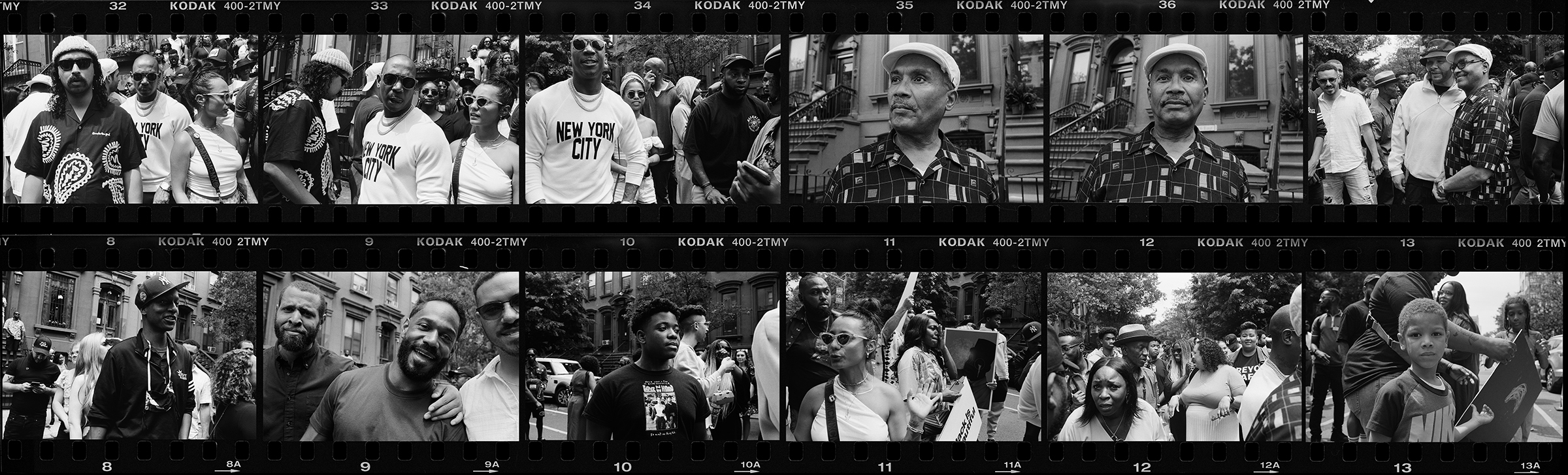

Fat Joe, who was photographed by Gordon Parks in the 1998s A great day in hip-hopstanding next to George Butler, who was photographed in Art Kane’s 1958 A great day in Harlem.

Gioncarlo Valentine for TIME

It wasn’t that long ago that the number of blacks in the NFT community was close to zero. When Oakland-based photographer Brandon Ruffin became interested in the space in November 2020, he found “not even a few” black voices in NFT conversations on the audio chat app Clubhouse. “It would make you ask, ‘Is this a place for us?'” he recalls.

But Ruffin, known as Ruff Draft, remained intrigued by the space, in part because it offered a strong alternative to the relentless flow of Instagram, one of the main platforms he used to showcase his work. “On Instagram, I felt more limited, like I really had to be rooted in the algorithm if I wanted to be relevant,” he says. “When I came to the Clubhouse and met other photographers, I felt inspired and freed from many things that didn’t matter. It helped me focus more on the art, and made some really good friends.” Ruffin sold more than $40,000 worth of NFTs in December 2021 alone.

The artists, along with various members of the community, came out for the photo recreation on the stoop on Tuesday, June 21.

Gioncarlo Valentine for TIME

Last November, chef and event organizer Manouschka Guerrier showed up to NFT.NYC—a series of lavish events that took the city by storm at the height of the bull market—and found she was often the only black woman in the room. “It was my Uber drivers or bartenders who would look at me and start asking me questions about NFTs,” she says. “I found myself aboard a lot of New Yorkers.” Little by little, Guerrier and others made a concerted effort to bring black artists and developers into the NFT space via social media and word of mouth. A community emerged.

Read more: As the NFT market explodes again, artists fend off old power structures in the art world

Encouraged by this growth, Guerrier became increasingly inspired by the space’s potential for decentralization and ownership, and the way it could open up a world where artists create freely, release their work to the public, and profit directly without the need for small intermediaries. . At the next NFT.NYC in June 2022, she had the idea to organize an event that would bring together a community that had previously only interacted digitally, plant a flag for its artistic primacy and link it back to a rich cultural past.

So she put out an open call for Black NFT artists and enthusiasts to come to Harlem on June 19 to recreate the iconic jazz and hip-hop stoop shots. About 90 showed up, from key artists at the forefront of the NFT movement, like Ruff Draft and Cory Van Lew, a painter whose colorful works have sold at Sotheby’s for hundreds of thousands of dollars, to entrepreneurs like Nait Jones, a founder of NFT music startup Royal. (Notable absences included: photographer Drift, who takes photos from the top of skyscrapers and has sold millions of NFTs, and curator Diana Sinclair, who runs the Digital Diaspora series, and hip-hop artist Latashá.)

Nait Jones, a founder of NFT music startup Royal, left, and rapper Ja Rule.

Gioncarlo Valentine for TIME

The event also drew an older, hip-hop-oriented guard who believe that NFTs will be just as powerful for them as they will be for a younger generation. Many of hip-hop’s foremost elder statesmen have jumped into crypto, including Jay-Z, Nas and Snoop Dogg. And in Harlem, a trio of beloved rappers who rose to prominence in the ’90s—Fat Joe, Ja Rule and Bun B—appeared to entertain the crowd and chat with younger artists. Former NBA star Metta World Peace, who launched his own NFT community in April and has long been involved in hip-hop culture, also arrived in style.

Ja Rule, who has several NFT ventures, spent most of his time at the event hyping up one of his protégés, NFT artist Nick Davis, who created the “Black is Beautiful” art series. “We’re so programmed to believe that only the art that was made years ago is the art that’s most valued. But so much art is being made today in the NFT and Web 3 space,” said Ja Rule. “My vision and dream is to have Nick be a household name like Basquiat or Rembrandt.”

Photographer Brandon Ruffin orchestrates the photo shoot with bending.

Gioncarlo Valentine for TIME

The Web 3 space is still far from equitable, both in terms of race and class. A recent study by blockchain data firm Chainalysis found that in several large crypto communities known as DAOs, less than 1% of all token holders hold 90% of the voting power. Back in Harlem, event attendees criticized the overwhelming whiteness of the NFT.NYC events downtown, and the tasteless ape noises emanating from ApeFest, an event hosted by the hyper-popular NFT collective, the Bored Ape Yacht Club.

Guerrier says she understands why the NFT room receives criticism, and would like to help reorient some of the goals. With the June event, she wanted to show an alternative vision for the future of NFTs, one that was not based on wild speculation, but artistry; which is common rather than extractive; that centers black culture rather than copying it for profit, as the jazz, rock, and hip-hop industries had done generations before. “There are some people who are only about money and influence. But for many of us in this room, it’s about community, art and love that prevail, she says. “For black people, generational wealth has eluded us for so long. Our creation of art and the way we express ourselves has inspired so many people, but we have not been financially rewarded. At least in this room, we get to do that.”

Kai Miller, a digital strategist, echoed her comments, pointing to NFTs as a potential solution to the exploitative nature of the music industry. “When you start licensing and scoring an album, you realize that many of your favorite Black artists don’t even own their masters. Why did Michael Jackson and Jay-Z have to buy their masters back?” she says. “In the NFT space, ownership is from day one.”

Artists and NFT enthusiasts showcase NFT art from the Harlem stoop.

Gioncarlo Valentine for TIME

As the group marched through the streets of Harlem, they carried posters of Davis’ vibrant artwork and sang “Black is beautiful.” Once there, it took a while for everyone to squeeze into Ruffin’s frame. In the end, it was Ja Rule who took command, using his booming voice to lead people into the shot. Many spectators watched, including George Butler, who was part of the original 1958 day as a child and recalled sitting for hours on the curb next to pianist Count Basie.

Fat Joe, who was at the shoot in 1998, reflected on the link between the two events. “Everywhere you looked, you saw hip hop royalty,” he said of the footage in 1998. “I see what Yeah [Rule] trying to do here with the NFT world: basically trying to tap into the DNA of what was – and what is going to be in the future.”

A Great Day in Hip-Hop, Harlem, New York, 1998 photographed by Gordon Parks.

Gordon Parks – Gordon Parks Foundation

More must-reads from TIME