Beyond payments, what opportunities lie in Nigeria’s fintech sector?

Since 2015, African fintech startups have raised over $3 billion across 722 rounds. During this time, Nigeria has often raised the most capital and in 2022 was responsible for 46.1% of the continent’s fintech funding. Digging further into the numbers shows that most of the country’s fintech startups play in the payments area, while the most valuable are expected in that area.

One reason for the rise in payments startups is the informal nature of the economy, which has spurred payment innovations. Recently, however, there have been calls from users and investors for entrepreneurs to focus on other fintech verticals.

Mayowa Kuyoro, partner and head of West Africa Financial Services at McKinsey & Company, is one such person. The growth of payments startups, she says, has been driven by necessity as people need convenient payment options.

“If you look at the macro level and see payments as a vertical, everyone has to exchange goods and services. Whether it’s cash or electronic, you have to exchange goods and services, and so payments are almost integrated into our everyday lives.”

But that is not the only reason why payments have grown so enormously. In 2012, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) launched its financial inclusion plan to reduce the number of financially excluded Nigerians from 46.3% in 2010 to 20% by 2020. Part of the CBN’s goal was to have the percentage of Nigerians with access to payment services grow to 70%. That has not happened despite a series of policies intended to accelerate financial inclusion. In addition, the creation of NIBSS Instant Payments (NIP) has also tracked developments in the payments sub-sector.

“One reason people have adopted account-to-account transfers is that we have instant payment systems. I remember when I lived in Australia, I was confused about what was going on with the banking system. I didn’t understand why it took two days before I saw the money paid into my account.

“There has also been a collective push for financial inclusion. When you have your store of value, and I use the term store of value very deliberately, in electronic form, it’s almost more convenient to make an electronic payment.”

But despite the growth recorded by payment startups, Kuyoro believes that startup founders need to start thinking about building solutions in other sectors.

“I think we need to have more startups going into other verticals beyond payments,” she says. “Payments make up the overwhelming majority of fintechs that we see in this market, and we need to see people who offer other financial services.”

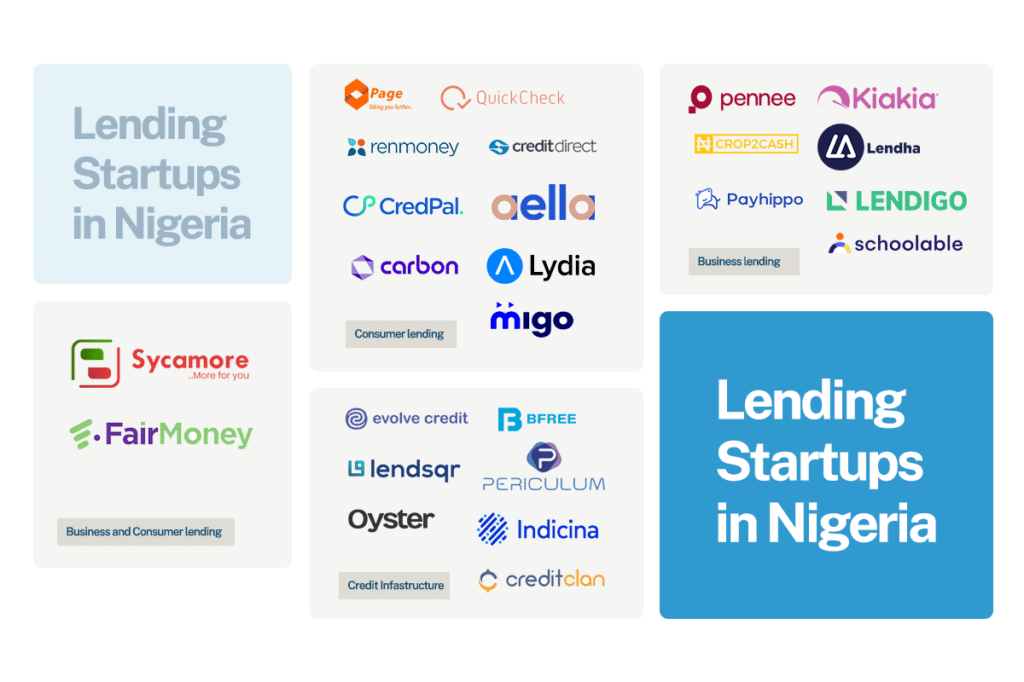

Two areas she identifies as potential growth areas are the lending and asset management sectors.

“There is a lot of informality today in the way people borrow, and I feel there is more room for innovation there to be able to provide credit to both individuals and small businesses.”

Access to credit remains a major challenge for individuals and businesses in Nigeria. According to the Credit Bureau Association of Nigeria (CBAN), only 4% of Nigerian MSMEs have access to credit. Individuals are no better off, as seven out of ten bank customers in Nigeria do not have access to credit.

Already, fintech startups are drawing on customer data to extend credit to Nigerians. However, more needs to be done if access to credit is to be extended to most Nigerians. Here, Kuyoro argues that the government can create policies that encourage startup founders to build solutions in other sectors. Just as the creation of an instant payment system drove the use of instant payments, governments must work to provide the necessary infrastructure upon which founders can build.

“What helped drive payouts was that the basic infrastructure was there. The government said: “We want to go cashless, so we have to have instant payments.” If we do more of those kinds of things where we get the infrastructure in place to help address some of the infrastructure voids that we have in our country, I think it might help people look at other verticals in the financial system. »

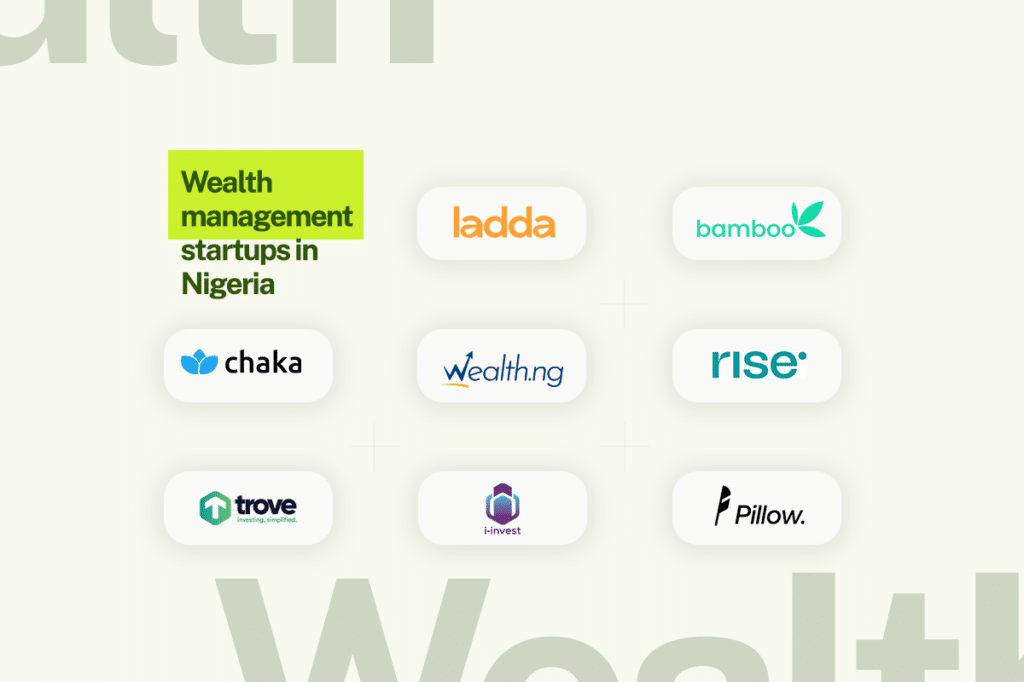

Wealth management startups, on the other hand, have slowly emerged since 2016. Startups such as Bamboo, Chaka and Risevest allow Nigerians to invest in foreign companies with as little as $10. Kuyoro believes that as Nigerians have more disposable income, they will demand wealth management solutions.

“I think that if we see the kind of growth that the IMF and the World Bank are projecting, people will become a little richer and therefore have a little more disposable income. Consequently, they may want wealth management solutions.”

Building the enabling infrastructure is not all the government can do, and Kuyoro adds that partnering with relevant stakeholders to achieve certain outcomes is necessary, as well as creating an environment that encourages innovation.

“One of the things that a country like Singapore has is sandboxes that enable startups and innovators to experiment in controlled environments. We have functional sandboxes that help people with innovative solutions to figure out how to extend other financial services to the population better?”

In January 2023, the CBN announced that the regulatory sandbox had gone live, with eligible businesses encouraged to apply. Considering that this is the CBN’s attempt at a regulatory sandbox, the outcome may give an insight into how the apex bank intends to offer regulatory support through sandboxes.

Between 2010 and 2020, Nigeria’s financial exclusion rate shrank by 10.4%. At least 35% of Nigeria’s adult population is economically excluded, and a KPMG report estimates that it will take approximately 40 years to reach a 10% economic exclusion rate. Kuyoro argues that increasing the economic inclusion rate in Nigeria requires work on factors such as gender equality and education.

“If you look at the numbers, they will tell you that those who are mainly excluded today tend to be women, tend to live in Northern Nigeria, and also tend not to be as educated as the median in the country. I think when you address some of the broader factors like gender equality and people having the agency to make decisions, etc., we can improve financial inclusion.”

While the focus is often on getting people access to a transaction account, she argues that financial inclusion goes beyond that, and financial service providers need to build products that meet customers’ needs.

“We need to think about financial inclusion beyond just having access to a bank account or a wallet, but having access to a full suite of financial services that speak to the needs of the people who will use them.”