Per Kristian Stoveland’s love letter to science fiction

Per Kristian Stoveland’s artistic mind inhabits the liminal space between the logical and the playful. A visual artist who fell in love with coding at a young age and co-founder of Oslo-based design studio Void, Stoveland has recently found a home for his love of generative art and graphic design in Web3. On January 18, 2023, he released his latest NFT project, The Harvest, on the generative art platform Art Blocks. With a current floor price of 7 ETH and more than 2,684 ETH in trading volume on the secondary market, Stoveland’s first major entry into the Ethereum blockchain has been well received by the NFT community.

But the artist’s recent foray into Web3 came somewhat unexpectedly. Specifically, it was on the heels of a passionate return to creating generative art that he had for some time put aside to focus on client-based work in his design studio.

Thanks to the blockchain, Stoveland has had to rethink the trajectory of not only his work, but also his artistic identity and career path. This identity has its roots in the towns and cities of Kenya and Zimbabwe, where he spent much of his childhood. Without that experience, Stoveland might never have taken art seriously.

NORAD, Montessori schools and family

When Stoveland was only two, his parents moved the family to Africa. At the time, his father oversaw Norwegian aid plans for water development in Kenya and Zimbabwe for NORAD. However, his parents were adamant that they did not want Stoveland and his younger brother to receive a typical Norwegian education for foreigners. Instead, they chose to send them to a local Montessori school.

“I’ve become more certain that my time at that Montessori school set a standard for me,” Stoveland explained to nft now with test prints of The Harvest hanging in the background of his home office. “In many ways, my brain works logically and analytically like my father’s. But being allowed into that school got me in a way that didn’t follow in his footsteps. That [education] set a foundation that has always kept me more on the creative or more playful side of things, even though my biology kind of screams for logic,” he said.

After returning to Norway as a teenager, Stoveland started a band with some friends. This serendipitously pushed him towards a career in design, as he decided to take on the task of creating the group’s album cover. Around the same time, he stumbled upon the world of coding. Stoveland fell in love with Adobe Flash, a program that used to dominate the Web2 world, as it had an impressive set of creative tools for building animation and interactivity into websites.

Over the course of a year, Stoveland made art as an active member of the international generative art community, which he says happily mirrors the generative art NFT community he sees on Twitter today.

“It’s funny, a lot of those people from the Flash heyday I 1676665307 recognize in the NFT community, such as Joshua Davis and a few others, Stoveland says of the historical review.

The road to NFTs

After graduating from the Oslo School of Graphic Design in the early 2000s, Stoveland worked as a designer and coder for several years before co-founding Void in 2015. It was in August 2021, when fellow Void co-founder Bjorn Staal released The Liths of Sisyphus on Art Blocks, that NFTs really got on Stoveland’s radar.

“I thought, I can do this [kind of work]”, Stoveland recalled of the early days of NFT exploration. “I did do this. Why did I stop?” Unfortunately, Stoveland’s work at Void tends to deal more with logistics and implementation and less with the conceptual or creative processes of the stunning installations they are known for producing.

But fittingly, much of what Stoveland does at Void is akin to making generative art; but instead of appearing on a computer screen, it appears in LED lights and project mappings and various forms of installations. Stoveland eventually leaned into NFTs as a medium to find his way back to a more “pure” form of generative art for himself rather than for a client. To this end, he says blockchain has enabled him to focus on a more self-involved and happily indulgent form of creative expression.

“I could post my art on fxhash, for example, whenever I wanted,” explained Stoveland. “There were a lot of things that were just easier. fxhash allowed me to learn a lot about where I want to go [with my art] and on the technical side of NFTs.”

“fxhash made me learn a lot about where I want to be [with my art] and on the technical side of NFTs.”

Per Kristian Stoveland

After releasing some smaller projects on fxhash, Stoveland decided to try his luck on Ethereum with a long-term and in-depth project. After months of experimenting with the code that would eventually become the basis of the project, Stoveland approached several well-known NFT platforms to see if they wanted to help launch the collection.

While he was met with a number of positive responses, he took a chance and rejected them. Reason? Art Blocks had approached him to curate his work, not the other way around.

The harvest

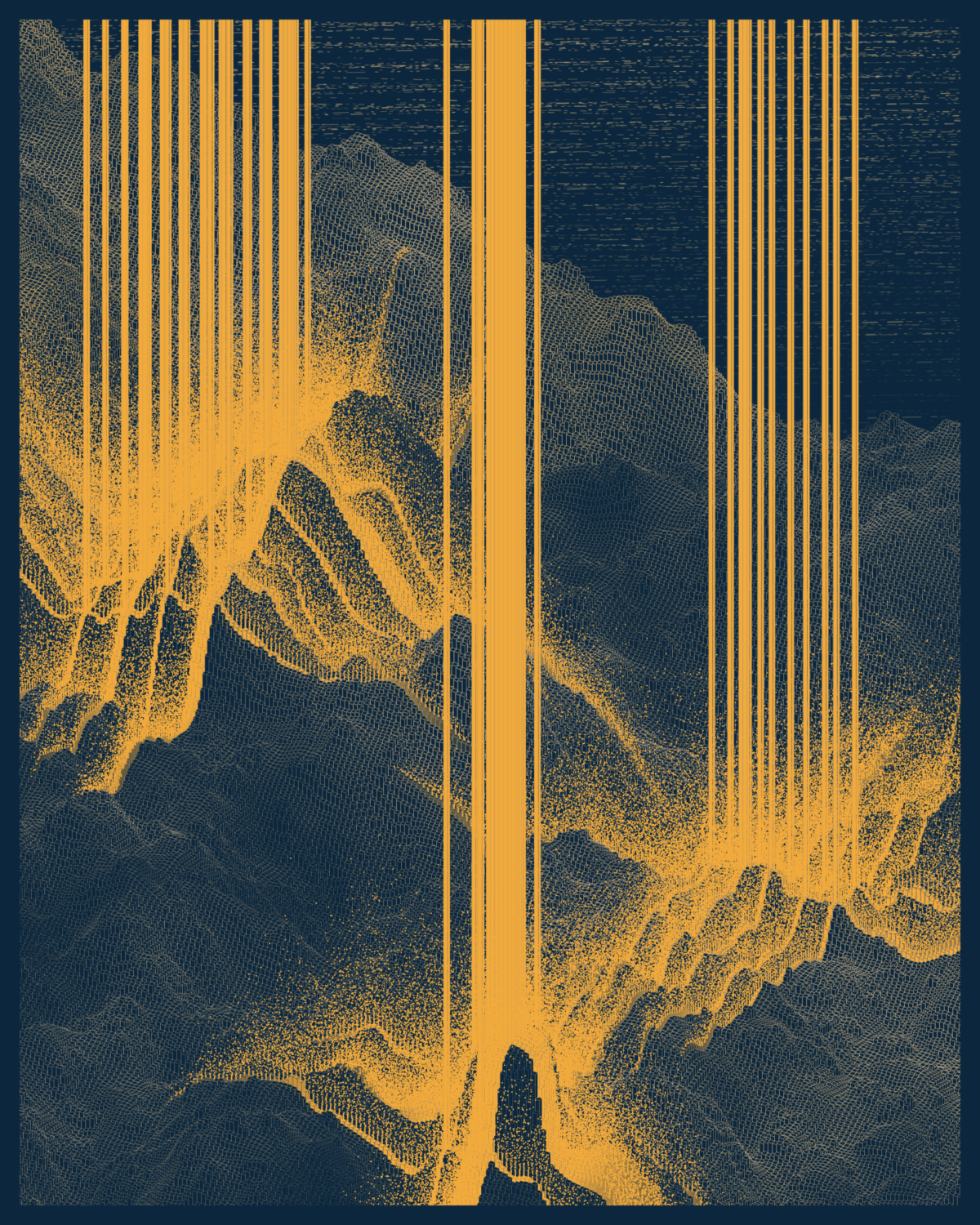

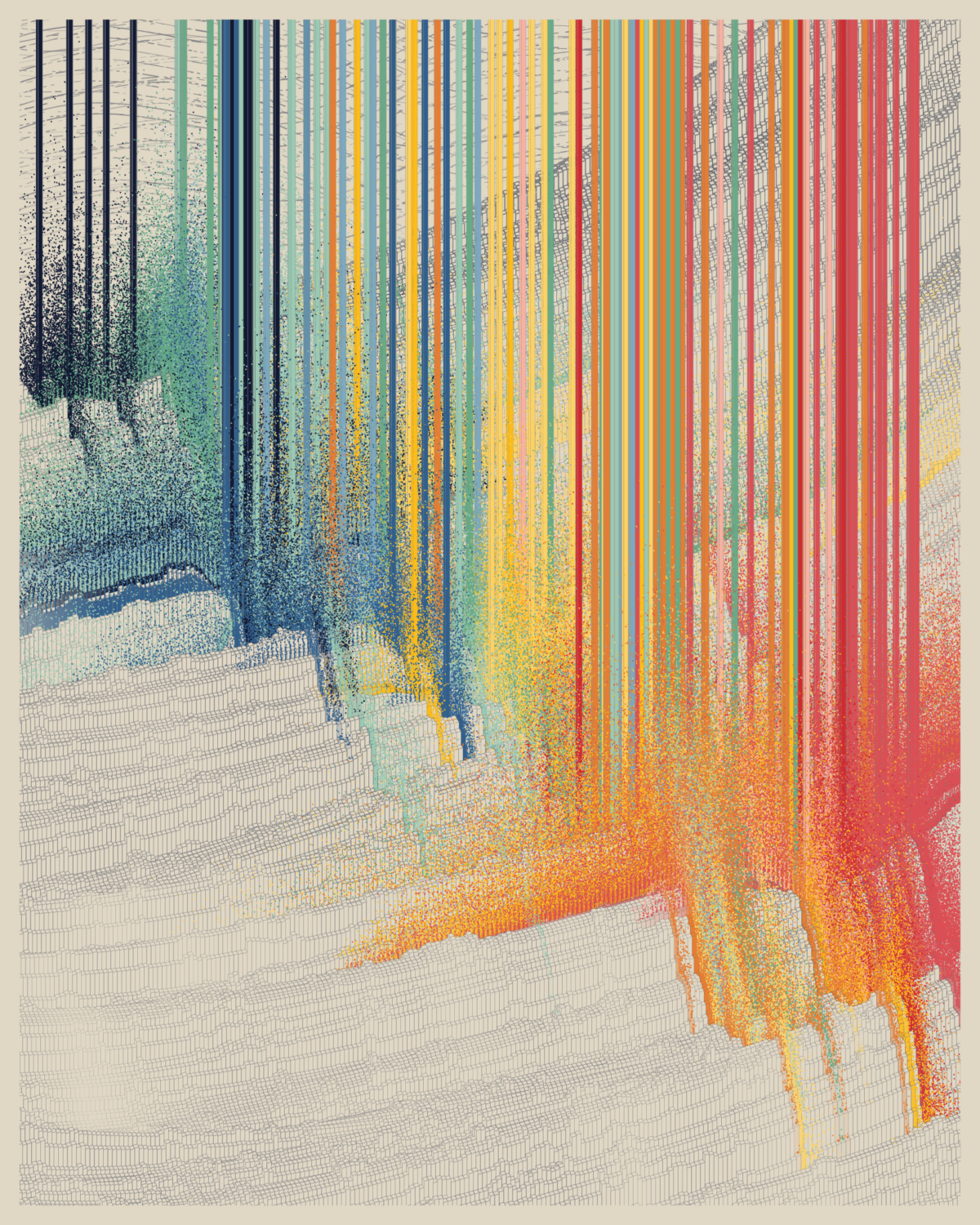

The project to appear on the generative platform was The Harvest, a series of 400 NFTs of digital landscapes with different color schemes with beams of light shooting out from their topographies. Launched last month, The Harvest’s synopsis describes a vague but inspiring tale of interplanetary beings (The Caretaker and its horde) preparing for an important occasion. It also gives a sense of heavenly awe to the reader.

The “cathedral-like” atmosphere and varied landscapes that define the collection’s visuals draw inspiration from science fiction artist Michael Whelan and architect and illustrator Hugh Ferris, reinforcing the idea of humanity’s insignificance in the grand scale of the cosmos.

And while Stoveland has kept the story behind The Harvest deliberately ambiguous, to potentially expand it in the future with more projects, he invites viewers to use their imaginations to play with what they think the story might be about themselves.

“I’ve always been very interested in sci-fi,” Stoveland said of the project’s genesis. “I’ve always thought that when I retire, I’ll write a sci-fi book. What I realized when I thought about doing these sci-fi books was that I might be able to tell the story, but not through books. Maybe I can make it [visual] art instead. Perhaps a next project could be based on the reaction of an antagonist to this caretaker.”

The collection features 19 different color palettes, each referencing either a famous science fiction tradition or universe: Arrakis, Serenity, Thoth, Nostromo, Moya and more among them. Stoveland named the palettes after creating them, spending a few nights considering which sci-fi tradition they made him think of when he saw them.

Sharp-eyed NFT collectors have taken notice that some of these palettes are actually more unique than others (almost unexpectedly), and tend to change hands consistently at double the collection’s floor price. The Nostromo and Sulaco palettes are two such rarities, which happened to be the palettes that Stoveland considered the “baseline” for the entire project.

Blockchain and generative art: a match made in heaven

Stoveland thinks the intersection between blockchain technology and generative art is particularly harmonious. The large file sizes of images and videos that non-generative visual artists tend to create do not mesh well with blockchain’s storage capacity – hence the existence of a system like IPFS.

But generative art, according to Stoveland, is “a level above that,” because the file sizes involved are often quite small, allowing artists to store their work directly on the chain. “There’s basically no limit to how big a collection can be without increasing its size in any significant way,” says Stoveland, with the average size of an NFT from his latest collection only taking up about 25 kilobytes of space.

The Blessings and Burdens of Success in Web3

The Harvest’s success has made Stoveland rethink how he approaches making art and what his future endeavors might look like. In fact, he says the project has been a significant “turning point” in his life.

“Before the project, [the goal] was just to finish The Harvest, and “I’ll think about anything after that,” says Stoveland. The project’s popularity, however, brought with it certain privileges and responsibilities he never had to consider before. “I’m at a point in my life now that I have to see the future maybe a year ahead. My stress level has been much higher than [normal]. I thought it would go down after the fall, but it has actually gone up,” he said.

However, Stoveland clarifies that this stress is not something outsiders have forced upon him. Rather, it stems from his own personality and the duty he feels to his supporters. “I feel very responsible when I do something. I almost want people to calm down, because what if something goes wrong? I feel responsible if someone loses money or, let’s say, floor tanks. And I feel that I am personally responsible for that thought. But it’s still a responsibility for something I’m very lucky to have,” he explained.

The way generative art code creates a collector’s NFT can also lead to an interesting new dynamic—one that artists must account for.

When someone tries to create a generative art NFT, that token’s code is pulled out of their browser. The token is then entered into the code and the final result is displayed. Consequently, an artist must guarantee that their code will result in the same visual result every time a token is generated (if such variation is not something they are after). In fact, part of Art Block’s process involves a person taking a particular token from a generative artist’s upcoming collection and displaying it on different browsers and computers to ensure NFT is consistent across the board. And so Stoveland struggles with new technical and community-based obstacles.

By his own admission, Stoveland is not a “social media guy”, and the NFT community’s heavy reliance on Twitter and online engagement is something he is still very much used to.

“It all feels surreal and insane, to be honest,” Stoveland said. – I am very satisfied with the project. I think it looks lovely. But people who put that value in it are just feeding a kind of impostor syndrome. Again, I realize this is an extremely lucky position. It’s a very interesting mix of stress and gratitude.”

This appreciation is evident in the serious way Stoveland considers the future of his work and what it means to have a relationship with collectors and admirers in Web3, a consideration that is often missing in the room. Also, in an effort to reward its newfound collector base, Stoveland is making signed physical prints available to anyone who has an NFT from The Harvest collection.

But it is his future work that will most likely be the greatest gift of all. And while the impostor syndrome has a hard time responding to reason, it is undeniable that Stoveland has breathed fresh life into the generative art scene in Web3. Now let the man take a break from Twitter. He has earned it.